. | .

. | .

LAWRENCE — Researchers at the Center for Remote Sensing and Integrated Systems, headquartered at the University of Kansas, have received almost $1 million from the National Science Foundation’s Major Research Instrumentation program to design and build an adaptable radar system for long-range unmanned aerial systems.

With the new radar, scientists at CReSIS, the KU School of Engineering and other researchers will be able to gather more complete data on ice-sheet thickness in some of the most remote expanses of Antarctica and Greenland. The new system also could improve ice-discharge estimates and make it easier to routinely monitor snow cover on sea ice.

“This builds off what we already do at CReSIS with our sounding radars,” said lead researcher Emily Arnold, associate professor of aerospace engineering at KU. “The unique thing about the radar system we're going to develop is it’s reconfigurable. It will have a common digital back end but a swappable RF front end. This radar will be able to operate over a much wider range of frequencies. Instead of having to design and develop three discrete systems, we can just design this one. Then, we could do a variety of missions looking at different parameters.”

The radar eventually could be deployed to a range of medium-sized UAS platforms from various manufacturers. But Arnold and her collaborators first will partner with Hollywood, Maryland-based Platform Aerospace. They plan to adapt the radar to the Vanilla UAS — a system ruggedized for cold weather that could greatly extend the range of research flights operated by scientists at CReSIS and other collaborations.

“We're designing it to be platform-agnostic, meaning ideally you could put it on any small UAV platform,” said Arnold, who earned a recent CAREER award to integrate miniaturized radars onto a small UAS helicopter. “But this vehicle from Platform Aerospace has set several endurance records. By partnering with them on this grant, our plan to integrate our system into the Vanilla UAS. One thing you can't really standardize is the antennas. You have the radar system — the electronics that generate the signal — but then you need something to emit that energy. That's where the antenna comes in, but those tend to be more customized based on hard points available on the aircraft. So, we’re designing custom antennas for the Vanilla aircraft to support these operations.”

Most design and fabrication work on the new system will happen in-house at KU, according to Arnold. Six other senior KU faculty associated with CReSIS will join the project, along with collaborators at Michigan State University and experts from private industry.

“The electronics will be fabricated over at Nichols Hall on west campus,” Arnold said. “The antenna and pods are going to be made out of composite materials, so we'll be able to fabricate those in our aerospace Composite Material Lab.”

Next, the KU researchers will team up with Platform Aerospace to integrate the radar into the Vanilla UAS and begin test flights of the systems at the firm’s proving grounds.

“They’ll be responsible for operating the vehicle while we operate the radar,” Arnold said. “For our initial flight test, we usually just fly over the ocean because the ocean provides a nice specular target to calibrate our systems — we'll most likely fly over the ocean on the East Coast at one of Platform’s facilities.”

After assessing the new radar system’s operational readiness, the specialized UAS would take to the skies over Antarctica.

“For an initial field deployment, we’ll probably deploy out of McMurdo Station in Antarctica, which is the primary American base — they have established flight fields, and this is a well-controlled environment to deploy the vehicle from,” Arnold said. “But also under this grant we could spin off a lot of international collaborations, working with people from different countries who work from bases all over Antarctica. If we're collaborating with them, we could operate from almost anyplace that has an appropriate runway for us across the continent. There are some international collaborators that we're starting to talk to with about this — and we'd like to expand to more remote deployments.”

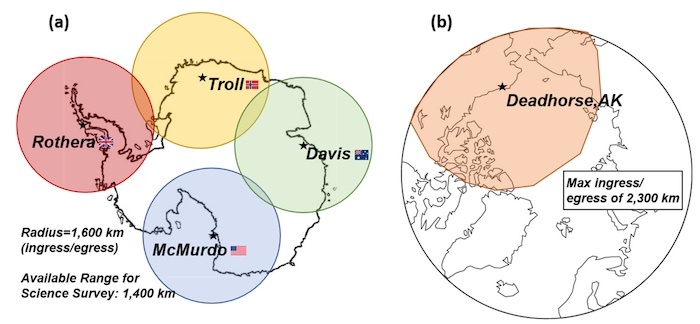

Such collaborations would allow researchers access to “highly remote Arctic and Antarctic regions at a much lower cost point than any manned platform,” according to the KU/CReSIS team. Fully loaded, the Vanilla platform can fly four days straight, although weather can often cut this short. Flying for two days, the Vanilla would cover about 2,850 miles, typically flying a gridded survey over a target. This range will give researchers access to “most regions with the largest data gaps” and extend their ability to monitor Arctic sea ice.

Arnold said the NSF grant also will support training of students at KU who will adapt the modular radar to the Vanilla UAS.

“I teach an aerospace manufacturing class, so I could take that pod, give them an outline of what it needs to look like, and then they would do design work as part of a class project,” Arnold said. “They would design all the details, analyze it to make sure it can withstand flight loads, and then actually fabricate a prototype. That's beneficial for both the students and the research project. You get a head start on the engineering and basically just throw a tiger team at the problem. From the students’ perspective, it's great because what they come up with has real-world applications. Maybe someday they might see a news story, and they'll say, ‘Hey, that looks like our pod design!’”

KU personnel working on the grant include Richard Hale, chair and Spahr Professor of Aerospace Engineering and associate director of CReSIS; Carl Leuschen, professor of electrical engineering & computer science and director of CReSIS; Fernando Rodriguez-Morales, senior research scientist at CReSIS; John Paden, associate scientist and deputy director at CReSIS; and Leigh Stearns, professor of geology. Other collaborators are John Papapolymerou of Michigan State University and Anthony Jones of Platform Aerospace.

Top image: Possible coverage maps for two-day missions with the Vanilla UAS across the (a) Antarctic (b) Arctic. The Antarctic missions assume a maximum range of 1,600 kilometers to the science target and a gridded survey of 1,400 kilometers of the target. Arctic missions simple assume and out-and-back mission. Credit: Arnold, et al.

Top right image: Emily Arnold of the University of Kansas will adapt a new configurable radar to the Vanilla UAS — a system ruggedized for cold weather that could greatly extend the range of research flights operated by scientists at CReSIS and other collaborations. Credit: U.S. Navy photo by Construction Mechanic 2nd Class Michael Schutt

Image: Echogram of six crevasses in the Arctic Peninsula's Wordie ice shelf in the Antarctic. Using the proposed radar flying on a UAV in grid patterns, similar echograms could be used to characterize the width and depth of crevasses in the remotest parts of Antarctica.Credit: Arnold et al.

Original source can be found here.

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up